I love you, but I don’t like you.

I love you, but I don’t like you.

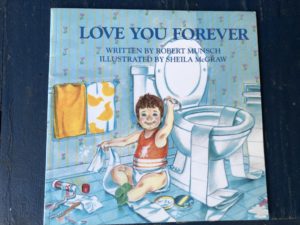

It’s a blasphemous remark to make about your own children, but I must confess that it’s the way I’ve been feeling lately as I plod through a particularly challenging stage with my boys. I felt exceptionally guilty about this sentiment as I was cleaning out the boys’ bookshelf and dusting off our tattered copy of “I’ll Love You Forever” that sings this refrain:

“I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always, as long as I’m living, my baby you’ll be.”

I’m sure you can recall this classic children’s book by Robert Munsch, the one that is notorious for making hormonal moms of newborns cry despite the borderline creepy image of a gray-haired woman driving to her grown son’s home with a ladder, climbing in through his window, and rocking him in his sleep. This lullaby is sugary sweet and touching and undoubtedly true. Of course we will love our babies forever, deeply and fiercely. But it is exactly this intense love and devotion to our children that can make us temporarily not LIKE our children as they go through certain stages, phases where they are trying on annoying behaviors, pushing limits, and seemingly doing everything within their power to agitate you.

There was a time when the annoyances were not intentional, when their moodiness or tantrums were byproducts of deficiencies in basic human needs (ie: sleep debt, hunger or itchy pajamas.) But then there comes an age when your children catch on to the fact that they are individuals, separate from you and possessing the superhero-like power of transforming you into a crazy lady, making your head spin Exorcist-style as you exude the entire spectrum of human emotions in a span of 5 minutes. There is a rush that must come from the epiphany that you can get under the skin of a grown adult who once seemed omniscient and invincible.

For my boys, in this particular unlikable stage, they’ve discovered my Achilles heel: potty talk. I know it’s developmentally appropriate for them to explore bawdy humor and it’s arguably even genetically-etched on their Y-chromosome, but I still struggle to manage the constant string of words inappropriate for the dinner table and really every other corner of civilization that we visit. The words “butt” and “poop” and “toilet” are attached to every phrase imaginable. Some make contextual sense and are used with correct syntax and grammar: “I need to go poop!” announced proudly in between bites of salad at dinner. But often they are just senselessly strung together to get a giggle from brother: “Hey you, toilet mommy,” or random chants of “my butt, my butt,” complete with little tushee wiggles that just aren’t cute anymore.

To add insult to injury, my boys are belly-laughing together and bonding over how much they are driving me crazy. It seems that the more irate and irritated I get, the more joy and brotherly love exude from this pair of bozos. I know what you are thinking. There is an easy solution, right? Just don’t react. Ignore them and they will lose interest. While this seems logical, I am just not able to do this. It is because I LOVE them so much that I feel this insatiable need to LIKE them too.

My youngest just started school, so this is the first time that they are both away from me for the bulk of the day. In the limited hours that I am with them, I want to enjoy them. But I find myself losing my mind as they unite in brotherhood on a vendetta to send me out of the room. Is this their way of asserting their independence? Of cutting the cord? Of pushing me to the brink, so they can work through the process of becoming stinky, gross boys that have personalities that starkly diverge from mine? Possibly. Probably. I’m still searching for coping mechanisms, but for now I suppose I will just keep loving them.

But I don’t have to ALWAYS like them.

Love this, girl! Speaking of girls, mine is fond of talking about “Poop Sandwiches” anytime anyone brings up food! Such a lady.

Brought me a big smile. And it is actually awesome that they are bonding together over this. Ah, the magic of siblings!

Comments are closed.